Codex Sinaiticus and the Critical Text | Was the Original Bible Corrupted and Restored?

Disinformation (IRONIC)

In the mid-19th century, a German scholar sponsored by the Russian Empire smuggled a supposedly ancient book out of Egypt. It was declared to be the oldest Greek Bible in the world, even though it was actually a forgery that intentionally corrupted the scripture.

This fake Bible was used by a cabal of occultist scholars who conspired to mass-produce new age Bible translations as part of a diabolical agenda to usher in a new world order.

Wait a minute. Let's take a step back. What you just heard is an example of the sensationalist rhetoric you might encounter from some staunch defenders of the traditional text of the New Testament. But conspiracy theories that falsely slander Bible scholars, translators, and publishers don't really do any justice to the Bibles being defended by these outrageous claims.

Dispelling Conspiracy Theories

So let's dispel some common misconceptions as we explore the history of modern Bible scholarship. If you're a staunch King James-only advocate, you may be sharpening your pitchfork already. And if you're on the other side of the debate, you may expect a thorough endorsement of your favorite Bible version.

And if you're new to this controversy, you may be wondering what all the fuss is about. Feel free to leave constructive criticism in the comments, and let us know which Bible version you prefer and why. But please be civil. And if you want to see more videos like this, please hit the like button and subscribe to the Cross Bible YouTube channel. Now let's dive in.

Recap on the Received Text

Previously, we explored the history of the Byzantine Text, the backbone of the so-called "Textus Receptus," also called the "Received Text" in English. This is the traditional form of the New Testament, widely considered to be the one true Bible version.

Check out our last video for the in-depth history.

The process of compiling the received text took over a century, during which scholars compared multiple manuscripts to determine the correct wording to use for the first printed Greek New Testament. This discipline, known as textual criticism, involves the critical evaluation of differences between manuscripts called textual variants.

The goal of textual criticism is often described as the reconstruction of the "original text," but opinions vary on how to define the original form of the New Testament because our earliest complete copies are centuries removed from the original writings, known as the "autographs."

The Early Critical Period

In the 16th and 17th centuries, most available Greek manuscripts were from the Byzantine textual tradition, so the text that scholars managed to reconstruct from the materials available to them closely mirrored the Byzantine Text, which has relatively little textual variation. From the perspective of those Renaissance-era scholars, they had managed to compile the "original" text of the Greek New Testament, which was the status quo in all printed Bibles until the 19th century.

Now let's shift focus to our timeline of the Bible feature to illustrate how Bibles began to shift away from the Received Text.

If you want more detailed instructions on the navigation features of the timeline, you can go back and watch one of our previous videos for a more detailed demonstration.

In the 18th century, three German scholars, all named Johann (Bengel, Semler, and Griesbach), pioneered a genealogical method for categorizing New Testament manuscripts into families, or what we now call "text-types". This approach was further developed in the 20th century by British scholar B.H. Streeter, who grouped manuscripts into the major families you see reflected on this timeline: Alexandrian, Western, Byzantine and Caesarean.

Note that all New Testaments produced during this period were reprinting the Received Text, which had reached its final form in the 17th century with the publication of the Elzevir Bible.

This text was universally regarded as the standard by which all manuscripts were measured. Any reading that didn't match it was a 'textual variant' by definition. Even though scholars were continually expanding the catalog of known textual variants and advancing the methodology of textual criticism, no one dared tamper with the body of the text in printed editions, but eventually 18th-century scholars began to favor readings found in the Alexandrian text-type.

Shorter readings were generally preferred by textual critics, because they were difficult to explain as intentional omissions by copyists, and when compared to the longer Byzantine Text, the Alexandrian Text often lacks words, phrases, or even whole sentences.

As a result, modern Greek New Testaments have removed 16 whole verses from the body of the text, sometimes relegating them to footnotes. This has understandably caused a lot of controversy.

| # | Verse | Reason for Omission |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Matthew 17:21 | Harmonization with Mark 9:29. |

| 2 | Matthew 18:11 | Parallels Luke 19:10, possibly added later. |

| 3 | Matthew 23:14 | Found in Majority Text, absent in Alexandrian witnesses. |

| 4 | Mark 7:16 | Lacks early manuscript support. |

| 5 | Mark 9:44 | Harmonization, repeats verse 48. |

| 6 | Mark 9:46 | Harmonization, repeats verse 48. |

| 7 | Mark 11:26 | Found in Textus Receptus, absent in early sources. |

| 8 | Mark 15:28 | Added based on Isaiah 53:12. |

| 9 | Luke 17:36 | Matches Matthew 24:40, possibly added later. |

| 10 | John 5:3b-4 | Marginal note incorporated into later texts. |

| 11 | Acts 8:37 | Liturgical addition. |

| 12 | Acts 15:34 | Explanatory gloss, not in early sources. |

| 13 | Acts 24:6b-8a | Textual expansion. |

| 14 | Acts 28:29 | Omitted from key Alexandrian manuscripts. |

| 15 | Romans 16:24 | Present in Textus Receptus, absent in early sources. |

| 16 | 1 John 5:7b-8a | Trinitarian interpolation added in Latin manuscripts. |

The Critical Period

The 19th century marked a new era in Bible scholarship, with the publication of three groundbreaking editions of the New Testament that officially parted ways with the Received Text in favor of the Alexandrian Text.

The first was Karl Lachmann's 1831 edition, published in Berlin, which took him five years to produce, relying on Greek manuscripts written in uppercase Majuscule letters, the most ancient copies available.

Since he didn't believe it was possible to reconstruct the "original" text in detail, his stated goal was specifically to reconstruct the text he believed was standard in the fourth century. This created a rift among scholars and clergy.

One vocal advocate of the Byzantine text who opposed Lachmann was an English textual critic named Frederick Scrivener, known for revising the received text in 1894 to align the Greek more closely with the English of the King James Bible.

Scrivener critiqued Lachmann for relying on slim manuscript evidence and ignoring the Byzantine Text. Decades after Lachmann's shot across the bow, two more challengers of the traditional text entered the fray.

One was a British scholar named Samuel Tregelles, and the other was a German scholar named Constantine Tischendorf. Both of them argued that the Byzantine Text was inferior and late, favoring the Alexandrian Text in their critical editions of the Greek New Testament.

But despite Tregelles' meticulously prepared magnum opus that took him 15 years to produce, Tischendorf overshadowed Tregelles thanks to his discovery of one of the world's oldest complete Greek Bibles, Codex Sinaiticus.

The World's Oldest Bible

Constantine Tischendorf found this ancient Bible in the library of Saint Catherine's Monastery at the foot of Mount Sinai in Egypt, where, according to Tischendorf's dubious account, the librarian was nonchalantly tossing reams of ancient papyrus into a fire to stay warm. According to Tischendorf, he saved the world’s oldest bible from certain destruction.

In 1853, Russian Tsar Alexander II sponsored Tischendorf's trip back to the monastery to find the rest of the Bible, which ended up comprising a complete New Testament written in uppercase Majuscule letters, the only one like it in the world.

In 1862, a Greek paleographer named Constantine Simonides came forward, claiming that he single handedly forged the codex decades earlier, an audacious claim still hyped up today, even though it's widely rejected by scholars. This massive Bible, now residing in the British Museum, has been dated by experts the world over to the fourth century A.D.

The codex consists of over 730 leaves of parchment paper, which required the slaughter of hundreds of animals to produce. Another noteworthy feature of the codex is that it's the most heavily corrected Bible in the world, featuring over 20,000 handmade corrections by multiple scribes over several centuries.

In many instances, the correctors appear to be harmonizing the codex with other manuscripts.This makes Codex Sinaiticus similar to a text-critical edition in its own right. Tischendorf was so enamored with this codex that he assigned it the symbol of the Hebrew letter 'aleph', to ensure that it would always be sorted to the top of lists of manuscripts that are normally represented by Greek letters.

His discovery motivated him to update the eighth edition of his Greek New Testament in over 3,000 places, to conform with Codex Sinaiticus. And this era of Alexandrian dominance of New Testament scholarship culminated in the 19th century with a 28-year project undertaken by two Anglican scholars, Brooke Westcott and Fenton Hort.

The critical edition of the New Testament, completed by Westcott & Hort in 1881, sealed the fate of the Received Text in academia. It’s typically referred to by the hyphenate “Westcott-Hort” or the abbreviation “WH”. They shared Tischendorf’s enthusiasm for Codex Sinaiticus, but relied primarily on a similar manuscript called Codex Vaticanus.

In fact, they were so zealous for these two particular manuscripts that they coined the term “neutral text” for them to show that they were a cut above other generic Alexandrian witnesses, declaring that readings from these two manuscripts should be accepted as “the true readings until strong internal evidence is found to the contrary”.

In 1881, Westcott & Hort spearheaded the English Revised version which was the first English translation to revise the King James Bible on the basis of modern scholarship, relying on Westcott & Hort, along with Tregelles. One vocal opponent of this project was an Anglican priest, John Burgon, who fiercely defended the traditional text in the face of what he deemed to be an unreasonable deference for Codex Vaticanus, which he said was “the reverse of trustworthy”.

Attacks against Westcott, Hort and Tischendorf are still ongoing over a century later because their methods and reconstructed texts were very influential in the early 20th century. By all accounts, these men had sincere beliefs and pure intentions. Without getting into details, suffice it to say that modern scholarship has moved past the era of Westcott, Hort and Tischendorf.

The Egyptian Papyri

After the discovery of Codex Sinaiticus, Egypt continued to serve as ground zero for archaeologists to unearth ancient biblical manuscripts of both the Old Testament and the New Testament, written on papyrus and preserved in the dry climate. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, three collections of papyri had a tremendous impact on biblical scholarship: the Oxyrhynchus Papyri between 1896 and 1907, the Chester Beatty Papyri in the 1930s, and the Bodmer Papyri from the 1950s.

The discovery of these papyri provided evidence supporting the Alexandrian text-type, which one might expect from manuscripts found in Egypt. Even though Byzantine copies still make up a firm majority of later manuscripts, the Egyptian papyrus fragments now make up a majority of early witnesses used by modern scholars to reconstruct the text of the New Testament.

Whose Bible Is More Original?

In 1898, a German scholar named Eberhard Nestle compiled a critical edition of the Greek New Testament, which would end up becoming what we now call the Critical Text. He did this by simply comparing the two major critical editions of the 19th century, Tischendorf and Westcott-Hort. Since these two editions are very similar, he employed a third critical edition to resolve conflicts between them, first using the text of Weymouth before transitioning to Weiss.

Nestle referenced textual variants in the footer of each page, a section known as the "critical apparatus" or "textual apparatus". His text-critical Footnotes initially used abbreviations for critical editions to show where each reading came from. Nestle continued improving the apparatus of his New Testament until the 10th edition in 1913, when he passed away and his son Erwin took over as editor.

By the 13th edition in 1927, Erwin managed to add important manuscripts to the apparatus, using the work of late German scholar Hermann von Soden. In 1952, Kurt Aland joined the project as co-editor, expanding the apparatus further and checking it against original manuscripts.

The collaboration between Nestle and Aland led to the hyphenated title Nestle-Aland, abbreviated as "NA". Because the critical apparatus of the Nestle-Aland was so extensive, in 1955, the United Bible Societies put together a committee to produce a simplified critical edition for Bible translators.

Their first two editions, in 1966 and 1968, abbreviated as UBS or GNT, were substantially different from the Nestle-aland text. But in 1979 there was a major update to both editions, after which they shared the same base text. In these corrected editions, many readings inherited from the 19th century critical editions were abandoned in favor of early manuscript evidence.

This marked a transition from the period when scholars preferred Alexandrian readings by default to a period of so-called "eclecticism," which is basically the practice today. Modern scholars may choose textual variants from a variety of early manuscripts, regardless of their assigned text-type. The timeline of the Bible represents these mixed eclectic texts with the color gray, which includes nearly all modern Bibles based on the Critical Text. In 2010, the Society of Biblical Literature released the SBL version of the Critical Text, which simplifies the textual apparatus even further, referencing critical editions rather than ancient manuscripts.

Another noteworthy eclectic text is the Tyndale House Greek New Testament, which sets itself apart from the critical text by using the Tregelles Greek New Testament as its basis, avoiding the stigma surrounding Tischendorf and Westcott & Hort. The result of their text-critical methods is very close to the critical text, with some notable exceptions.

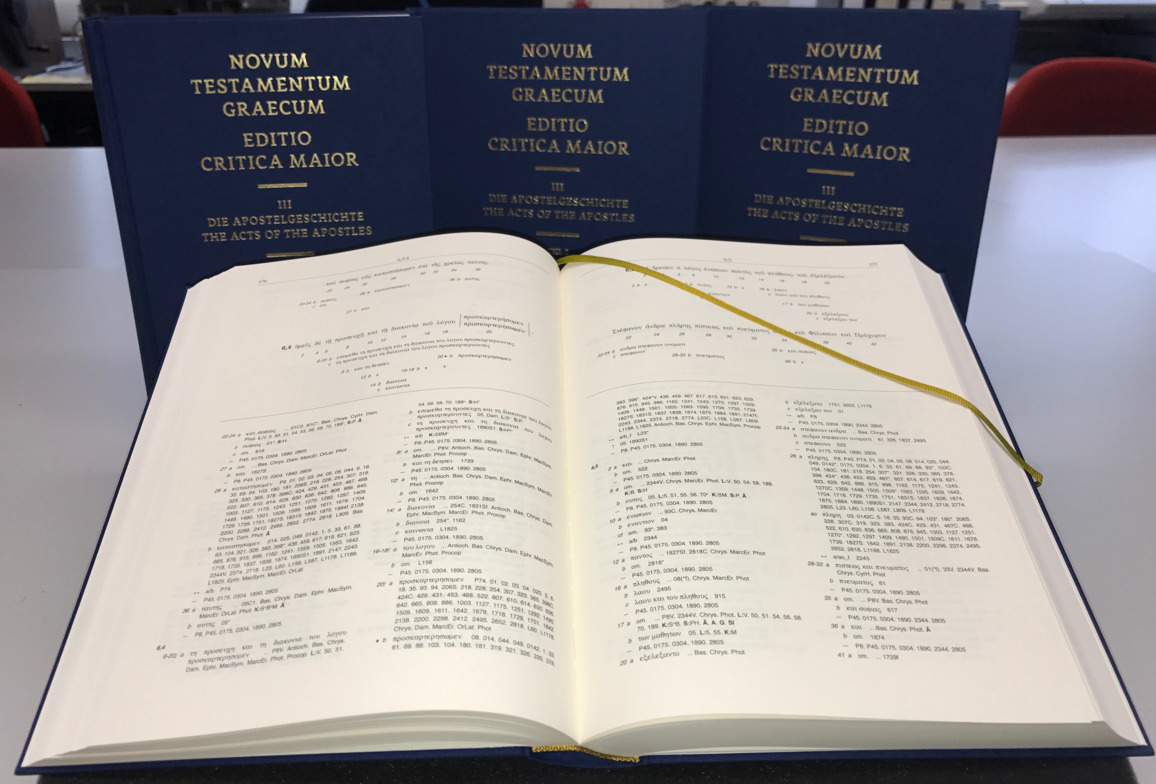

The latest development in New Testament textual criticism is the advent of the Editio Critica Maior (ECM), which utilizes a revolutionary computer-based system of evaluating textual variants, known as the Coherence-Based Genealogical Method (CBGM).

This brings us to an important disclaimer, included just above the legend on the timeline of the Bible. New Testament textual critics who adhere to the CBGM have largely abandoned the traditional categorization of manuscripts into "text-types" as presented on this timeline, preferring instead to group textual variants into clusters.

So far, the ECM has only released the Gospel of Mark, Acts of the Apostles, the Catholic Letters, and Revelation. And the editors of the Critical Text have already updated the Catholic Letters based on the ECM. The project targets the completion of the entire New Testament by the year 2030. So the practice of grouping manuscripts into so-called text-types may eventually be a thing of the past.

But cross Bible’s Timeline of the Bible is meant to visualize the traditional categories that gave rise to the Bibles we have today, because understanding them is still essential for understanding most scholarly resources that utilize modern textual criticism.

There is, however, one important exception: the CBGM still treats the Byzantine Text as a cohesive group that most likely developed over a long period of time. In fact, proponents of the CBGM have expressed a renewed appreciation for the Byzantine Text, since some of their reconstructions have vindicated certain Byzantine readings. But this isn’t likely to result in a pendulum swing back to the Received Text any time soon.

There are hundreds of thousands of textual variants in the New Testament, most of which are insignificant typos and obvious scribal errors. The traditional text of the New Testament has been prevalent throughout most of Christian history, and is found in many international Bibles.

In Christian communities with limited exposure to the Critical Text, most people are blissfully unaware that their Bibles may have been altered according to Bible scholars. Whereas readers of modern Bibles tend to be more aware of textual variants. if they notice missing verses and pay attention to footnotes.

Christians should not be polarized over controversies related to Bible versions, or suffer from anxiety over minor variations. Each side of this issue holds the sincere belief that the Bible they prefer is probably more "original". But the Bible one prefers tends to boil down to one's background and tradition.

The Alexandrian Text is based on a separate tradition, one that was likely prevalent in early Christian communities for many generations. It surely was not invented by modern scholars. And the Critical Text does include some textual variants and double brackets that the editors believe were not part of the original text, but are so well established in early Christian tradition that they have earned their place in the Bible.

If new manuscripts are ever discovered in the future that feature new textual variants scholars deem to be reliable, the Critical Text will be updated to reflect those new variants. That's simply how it works. But the received text is unlikely to ever undergo a revision, no matter how many ancient manuscripts are dug out of the ground.

Regardless of which side you're on, understanding the rich history of the Bible helps us appreciate the complexity of Scripture and the diligent work textual critics have to do.

Holistic Bible Study

Cross Bible will provide you with tools to help you make sense of the differences between Bible versions, even if you don't know Greek or Hebrew. Please visit crossbible.com and sign up for our mailing list for updates and early access to features. And if you can afford to support our mission, we would really appreciate your help to develop our software and continue producing Bible-focused content here on YouTube. Let us know your thoughts in the comments. Thank you for watching.

📖 Learn More - Sources and Recommended Reading/Viewing

Textual Criticism of the New Testament:

- Kurt Aland, Barbara Aland, "The Text of the New Testament: An Introduction to the Critical Editions and to the Theory and Practice of Modern Textual Criticism"

- Harry Sturz, "The Byzantine Text-Type & New Testament Textual Criticism"

- B.M. Metzger, B.D. Ehrman, "The Text of the New Testament: Its Transmission, Corruption, and Restoration" (4th Edition)

- Elijah Hixson, Peter J. Gurry, "Myths and Mistakes in New Testament Textual Criticism"

- Tommy Wasserman, Peter J. Gurry, "A New Approach to Textual Criticism: An Introduction to the Coherence-Based Genealogical Method"

- John D. Meade, Peter J. Gurry, "Scribes and Scripture: The Amazing Story of How We Got the Bible"

Corrections

-

5:10 It is an oversimplification to characterize the 16 'omitted verses' as a feature of the Alexandrian Text, as opposed to the Byzantine Text. We will delve into more detail in future videos to clarify the nuances we didn’t cover here.

-

7:24 Oops! The word "papyrus" was mistakenly used here in lieu of "parchment". Sorry about that.

-

10:00 Earlier English translations, such as those of Campbell and Kneeland, also revised the KJV based on "modern scholarship."

⚖️ Content Attribution:

Stock footage, music, and effects used in this video are licensed from Storyblocks and Envato Elements. Limited footage from other YouTube channels is used under fair use guidelines for transformative educational purposes:

⚠️ Disclaimer

The opinions and facts presented in this video are the result of private research by Bible study enthusiasts. This information has not been peer reviewed or published. It should be evaluated thoroughly and checked against reputable literature published in the field of Biblical Studies.

This video may contain short clips from other creators for transformative educational purposes. All external content is used under fair use guidelines (17 U.S.C. § 107) for commentary and critique. Full credit is given to the original creators, and viewers are encouraged to support the original work. If you believe proper attribution has not been given for your content used in this video, please contact us at [email protected] and we will rectify this by adding the appropriate attribution.

Affiliate Disclosure

As an Amazon Associate, Cross Bible earns a small commission from qualifying purchases made through the links in this article, which helps support our mission.